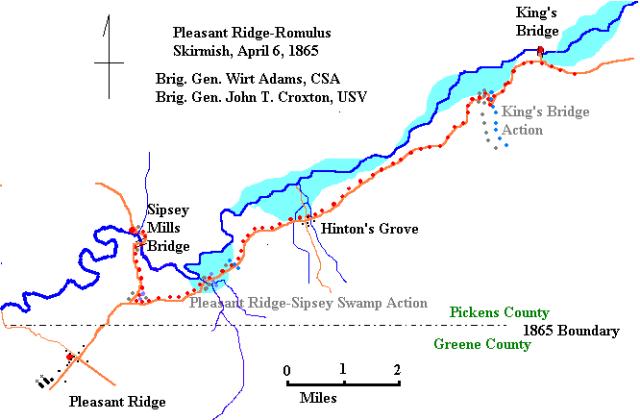

Sipsey Mills-King’s Bridge

(or Pleasant Ridge-Romulus) Skirmish

The Skirmish at Sipsey Mills Bridge, near Pleasant Ridge,

April 6, 1865

by Scott Owens Anrkee@aol.com, Updated

7/4/2005

On March 18, 1865, from Pickensville, Alabama, Brigadier General James R.

Chalmers, commanding a division of Lieut. Gen. Nathan B. Forrest’s Cavalry Corps

ordered all Mississippi cavalry on outpost duty around Jackson and Vicksburg to

report to Macon, Mississippi. This was in obedience to orders from Forrest’s

headquarters in West Point of the same date. On March 22, 1865, Brig Gen. Wirt

Adams, from Macon, informed Chalmers’ assistant adjutant general at Pickensville

that his command would not reach Macon before the 25th or 26th. On the 23rd of

March Forrest directed Chalmers to move Armstrong’s brigade with Hudson’s

battery from Pickensville to Selma via Finch’s Ferry on the 25th. This column

would have to pass over Sipsey Mills Bridge and through Pleasant Ridge. On the

same day Chalmers directed Brig Gen. Wirt Adams at Macon to hold his command in

readiness to move, with five days’ rations. On March 27, Lt. Gen. Richard

Taylor’s headquarters in Meridian expressed to Forrest, still in West Point,

that Gen. Wirt Adams’ brigade was in need of artillery, at least a section.

Forrest’s headquarters replied that "the Reserves" were then being inspected,

evidently reserve artillery, and would be sent to Adams. Perhaps it was at this

time that King’s Battery was attached to Adams’ command. At this same time,

Chalmers was moving from Pickensville to Selma with two brigades, and Forrest

himself was moving to Tuscaloosa with three brigades. All five brigades, and

attached artillery, passed over Sipsey Mills Bridge and through Pleasant Ridge.

It was Forrest’s intention to intercept the Wilson column from north Alabama

from Tuscaloosa. On March 29 Forrest was on the march, his headquarters on this

date being at Sipsey (Mills) Bridge, where two men, hastily convicted of

desertion, were shot. From here he directed Brig Gen. Jackson, division

commander of the force moving to Tuscaloosa, to guard that bridge and the

ferries above and below, as well as bury the bodies after two days.

Evidently on March 26 Adams received orders from Gen. Forrest to move his

command from Macon to West Point. Adams from Macon informed Forrest’s

headquarters on this day that he and his staff would take the first railroad

train up to make arrangements for encampment of the brigade. Adams indicated

that two of his regiments, which had arrived at Macon by that date, and Colonel

Scott’s command, Louisiana cavalry, began the march to West Point the evening of

the 26th. By the 28th Adams had his command encamped at West Point; Lt. Gen.

Taylor’s headquarters directed him on this date to report all enemy movements on

his front to Taylor as well as to Forrest.

On April 3 Taylor’s headquarters in Meridian reported to Adams the fall of

Selma. Taylor further directed Adams to move east, with his own brigade and Col.

John Scott’s Louisiana brigade, by way of Pickensville, with every available

man, taking only ordinance, cooking utensils, and hard bread; bacon would be

furnished on the line of march. Adams was to send a scouting party toward Selma,

through Greensborough and Marion, to locate the enemy and Forrest, Jackson, and

Chalmers. Adams was to join Forrest’s forces when located. Adams’ route of march

would pass through Columbus, Miss, where a Capt. Hough from Taylor’s

headquarters, provided further instructions. On April 4 Adams marched his

command from West Point to Columbus, arriving there at about 10 o’clock that

night. Adams’ command, after drawing arms and ammunition from the arsenal there,

left Columbus on the morning of April 5 and arrived in Pickensville that

afternoon where his 1500 cavalry camped.

The Federal brigade of Brig Gen. John T. Croxton, 1500 strong, which had been

sent by Wilson to Tuscaloosa to destroy the University with military factories

and facilities, left Tuscaloosa on the morning of April 5, 1865, at about 11

A.M., being observed by Henderson’s Scouts operating out of Romulus in

Tuscaloosa County. The Federals crossed the bridge into Northport, over which

they had assaulted to capture Tuscaloosa two days before. Before a company of

the 8th Iowa Cavalry could cross, however, the Yankees torched the bridge and

unwittingly stranded their comrades (who had to cross at Saunders Ferry west of

Tuscaloosa, further downstream). It was Croxton's intention to first feint

toward Columbus, Miss., then turn south to do damage to the Alabama and

Mississippi Railroad between Demopolis and Meridian, then join with Wilson's

Cavalry Corps.

The brigade proceeded west on the Columbus Road for seven miles, when (at Coker)

a detachment of 25 troopers and three officers under the command of Capt.

William A. Sutherland was sent on the Upper Columbus Road to extend the ruse of

marching on Columbus. This detachment turned south at Gordo toward Carrollton

and burned the courthouse. Sutherland was left with orders to join the brigade

at Jones’ Bluff on the Tombigbee.

Croxton, with the remainder of the brigade turned south to Romulus. Evidently

between the dispatching of Sutherland and Company D, and the brigade’s arrival

at Romulus later that afternoon, Croxton changed his mind about crossing at

Jones’ Bluff, and decided to march for Vienna, in Pickens County, which was a

closer ferry crossing, to gain the west bank of Tombigbee. The lost company of

the 8th Iowa Cavalry joined the brigade at about the Romulus area, having

crossed the Warrior at Saunders’s Ferry not far from there. The brigade turned

west toward Jena (in Pickens County at that time) and crossed Sipsey at King’s

Bridge (later known as Bailey’s Bridge) to Pleasant Grove, where they camped at

King's Store, in Pickens County.

At dawn the next morning, April 6, the Federal brigade continued south from

King’s Store "on the Road to Pleasant Ridge". After about six miles they came to

Lanier's Mill, southeast of Benevola and a mile downstream of the future Cotton

Bridge site. After a brush with Confederate Cavalry, likely Henderson’s Scouts,

the mill was burned and the brigade continued south. About six more miles

further was Jordan’s and Lanier’s Sipsey Mills (Lanier’s Mill), the largest

grist mill in Pickens and Greene counties. This tall brick structure had been

built on a steep bank of Sipsey in the 1850s by William B. Jordan and Thomas C.

Lanier of Pickens County.

At this place, which Croxton says was eight miles from Vienna, he learned of a

3000-saber force of Forrest's cavalry (a gross overestimate) was moving down Tombigbee from West Point, and that Wilson had taken and destroyed Selma.

(Actually a 1500 trooper brigade under Brig General Wirt Adams, CSA, had moved

to Pickensville the day before) Croxton reasoned that he just needed to go back

to Northport and find out where Wilson was rather than continue his mission

against the railroad. After looting the Confederate Commissary Depot at Sipsey

Mills of flour, corn meal, and bacon, and burning the mill, the brigade crossed

the bridge there, Sipsey Mills Bridge, and marched "several miles." (I believe

that this "several miles" is the position of the vanguard of the brigade column,

at which point Croxton would have found himself, being the commander and all.

The entire 1500 man brigade, marching in columns of twos as Wilson had trained

his corps, would take up a minimum of three miles on these narrow country roads)

At this point, about 9 A.M., they stopped and fed their horses. The 6th Kentucky

Cavalry was posted as rear guard, and Company F of that regiment were in the

vicinity of the mill and bridge for the entire two hours of this halt.

Undoubtedly other elements of this regiment were foraging in Pleasant Ridge,

securing the crossroads on the Selma-Columbus Road. During the next two hours,

patrols may have ventured into Pleasant Ridge and from Hinton's Grove toward

Clinton. Horses are known to have been taken in Pleasant Ridge, and two cousins

who lived between Hinton's Grove and Clinton were made prisoner by Croxton's

brigade: Phelan and Clement Eatman, both home on furlough from the 11th Alabama

Inf. and 7th Alabama Cav., respectively. After two hours the column continued its

northeast march back to Northport. Forrest's cavalry (a gross overestimate) was moving down Tombigbee from West Point, and that Wilson had taken and destroyed Selma.

(Actually a 1500 trooper brigade under Brig General Wirt Adams, CSA, had moved

to Pickensville the day before) Croxton reasoned that he just needed to go back

to Northport and find out where Wilson was rather than continue his mission

against the railroad. After looting the Confederate Commissary Depot at Sipsey

Mills of flour, corn meal, and bacon, and burning the mill, the brigade crossed

the bridge there, Sipsey Mills Bridge, and marched "several miles." (I believe

that this "several miles" is the position of the vanguard of the brigade column,

at which point Croxton would have found himself, being the commander and all.

The entire 1500 man brigade, marching in columns of twos as Wilson had trained

his corps, would take up a minimum of three miles on these narrow country roads)

At this point, about 9 A.M., they stopped and fed their horses. The 6th Kentucky

Cavalry was posted as rear guard, and Company F of that regiment were in the

vicinity of the mill and bridge for the entire two hours of this halt.

Undoubtedly other elements of this regiment were foraging in Pleasant Ridge,

securing the crossroads on the Selma-Columbus Road. During the next two hours,

patrols may have ventured into Pleasant Ridge and from Hinton's Grove toward

Clinton. Horses are known to have been taken in Pleasant Ridge, and two cousins

who lived between Hinton's Grove and Clinton were made prisoner by Croxton's

brigade: Phelan and Clement Eatman, both home on furlough from the 11th Alabama

Inf. and 7th Alabama Cav., respectively. After two hours the column continued its

northeast march back to Northport.

At 7 A.M. April 6 Adams’ command left Pickensville, moving southeast toward

Finch’s Ferry (over the Warrior near Eutaw). About 8-10 miles out of

Pickensville Adams set his command in motion at the double-quick (gallop) down

the Selma-Columbus ("Lower Columbus") Road toward Sipsey Mills. The brush with

Croxton’s column by Henderson’s Scouts near Benevola that morning must have been

reported to Adams about this time, indicating the whereabouts of the Federal

force reported moving toward Pickensville the day before. Shortly Adams entered

Bridgeville, on Lubbub Creek in southern Pickens County. No doubt by that time

he had also received reports of Sutherland’s detachment having burned the

courthouse and commissary depot in Carrollton; Adams may have been aware of no

further movement against Columbus, however, and considered Sutherland to be the

diversion for which it was indeed intended. Certainly the smoke from the burning

mills, visible by 10 A.M., would have revealed the Federal brigade.

At about 11 A.M. the lead squadrons of Adams’ cavalry, possibly of the 38th

Mississippi Mounted Infantry, assaulted across Sipsey Mills Bridge against

Company F of the 6th Kentucky Cavalry. Those who were not captured scampered for

the rear, precipitating a rout toward the wagon train of the brigade which was

heavy with barrels of flour and corn meal as well as stacks of cured bacon.

Among the wagons toward the rear of the column was the crowd of "contrabands,"

nearly seventy slaves who had left their plantations along Croxton’s march.

While the 6th was still trying to organize for a defense, Adams got enough

(probably two regiments) across the bridge to form a battle line and charge the

demoralized and dismounted 6th Kentucky. At about 11 A.M. the lead squadrons of Adams’ cavalry, possibly of the 38th

Mississippi Mounted Infantry, assaulted across Sipsey Mills Bridge against

Company F of the 6th Kentucky Cavalry. Those who were not captured scampered for

the rear, precipitating a rout toward the wagon train of the brigade which was

heavy with barrels of flour and corn meal as well as stacks of cured bacon.

Among the wagons toward the rear of the column was the crowd of "contrabands,"

nearly seventy slaves who had left their plantations along Croxton’s march.

While the 6th was still trying to organize for a defense, Adams got enough

(probably two regiments) across the bridge to form a battle line and charge the

demoralized and dismounted 6th Kentucky.

About this time a severe thunderstorm

began which continued into the night for most of central west Alabama. The 6th

Kentucky was hampered by the fact that they were quite under strength, having

lost some 35 at Trion a week earlier, and the 25-man Sutherland detachment was

from this regiment as well. Further, the 6th evidently carried single-shot

breech-loading carbines, rather than repeating Spencer carbines with which the

rest of the brigade was armed. Having found themselves in a open field,

dismounted with no cover, the harried troopers of the 6th pulled down bacon

stacks from the wagons and piled them up to form field fortifications from

behind which to fight.

Major William H. Fidler, commanding the 6th Kentucky,

attempted to concentrate his scattered companies near the brigade wagon train,

full of bacon, flour, and corn meal from the mill, and incidentally surrounded

by the crowd of "contrabands," slaves who had joined the Federal column as they

left their plantations along Croxton's march. As the Confederate charge crashed

into the rain-soaked Federal troopers, Maj. Fidler, who evidently was mounted,

was unhorsed and along with two privates was separated from the remainder of the

regiment. The three fled into the woods to the southeast of the melee to escape

capture at the hands of the Confederate cavalrymen. This was the last command of

Maj. Fidler, as he was lost aboard the Sultana.

The 2nd Michigan Cavalry, which was ahead of the wagon train in the line of

march, deployed four

companies toward the commotion. With two companies

dismounted on the edge of the field where the wagon train and the 6th Kentucky

had been overtaken by Adams' charge, and two mounted companies on the flanks,

the 2nd Michigan was able to halt the charge of the southern horsemen with the

heavy firepower of their Spencer repeating carbines, which were much superior to

the single-shot Sharps carbines or Enfield muzzle loading carbines used by the

Confederate cavalry. No doubt the repeating carbines, with sealed rim-fire

metallic cartridges, were more effectively worked in the falling rain than

single-shot weapons. Three troopers of the 2nd Michigan were wounded in the

fight with Adams. The remnants of the 6th Kentucky were able to pass through the

ranks of the 2nd Michigan and re-form. Adams evidently tried to charge the

Federals again, who withdrew as soon as the wagons and wounded were moved on

north along the road. In addition to twenty Federal prisoners, Adams captured

all the Federal brigade wagons including the headquarters baggage wagon with Croxton's personal effects, papers, and dress uniform. Fifty or 60 displaced

slaves were taken by the Confederates, as well as numbers of horses and mules. companies toward the commotion. With two companies

dismounted on the edge of the field where the wagon train and the 6th Kentucky

had been overtaken by Adams' charge, and two mounted companies on the flanks,

the 2nd Michigan was able to halt the charge of the southern horsemen with the

heavy firepower of their Spencer repeating carbines, which were much superior to

the single-shot Sharps carbines or Enfield muzzle loading carbines used by the

Confederate cavalry. No doubt the repeating carbines, with sealed rim-fire

metallic cartridges, were more effectively worked in the falling rain than

single-shot weapons. Three troopers of the 2nd Michigan were wounded in the

fight with Adams. The remnants of the 6th Kentucky were able to pass through the

ranks of the 2nd Michigan and re-form. Adams evidently tried to charge the

Federals again, who withdrew as soon as the wagons and wounded were moved on

north along the road. In addition to twenty Federal prisoners, Adams captured

all the Federal brigade wagons including the headquarters baggage wagon with Croxton's personal effects, papers, and dress uniform. Fifty or 60 displaced

slaves were taken by the Confederates, as well as numbers of horses and mules.

Major Fidler and his men, meanwhile, were hiding in the woods trying to elude

Confederate horsemen. They evidently took to the swamps around Shambley Creek.

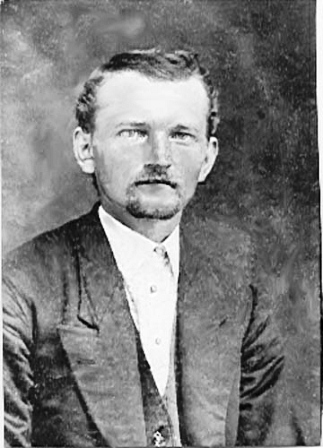

John D. Horton (photo at left), whose brother William owned Sipsey Mills, visited the skirmish

site and became aware of their presence in the swamps of Shamblee Creek. He

gathered up his "runaway dogs," trained to execute the provisions of the

Fugitive Slave Act, and returning to the scene of the engagement, the hounds

found the trail. One source says that the three were literally treed by the

pack. At any rate John D. Horton apprehended one officer and two privates of the

6th Kentucky Cavalry, and, according to some sources, with the aid of the local

home guard, delivered the three to the Sheriff in Eutaw to incarcerate them in

the Greene County Jail. It is possible that these were the last Federal soldiers

captured and confined as prisoners-of-war, at least east of the Mississippi.

(There is more to the story. Maj. Fidler made it aboard the

Sultana in Vicksburg, on which he was the ranking POW, and was lost with the

steamer north of Memphis.)

After the 2nd Michigan was able to withdraw, Adams reorganized his bloodied

regiments, brought up reinforcements, saw to his wounded, secured what prisoners

he could take, and carried on the pursuit, albeit in a heavy rain, described in

several sources as a "downpour" which lasted all afternoon and all night. One

primary source, a trooper of the 2nd Michigan, indicates that Adams "pitched

into" the rear of Croxton's column throughout the afternoon, so there must have

been some contact from time to time as the running fight moved north, along the

Pleasant Ridge-Romulus Road, which became increasingly impassable in the rain.

Near dusk, evidently around Romulus (though no source names the location) a

"very advantageous position" was found and two companies of the 2nd dismounted

and formed a line on the "brow of a hill.'" From this position the heavy fire

from the repeating carbines allowed this small force to withstand three charges,

mostly made in the dark and in this heavy rain, before Adams discontinued his

attacks. This Federal rear guard squadron fell back through swamps further

north, delivering a final volley in the dark to end contact, about eight

o’clock.

Both brigades camped in the rain in the area, supposedly in the Romulus

vicinity. Croxton is known to have occupied a particular dwelling in Romulus on

the night of April 6. Casualties amounted to 34 on each side for the whole day:

Croxton says he had thirty-two wounded and one killed, with one MIA, altogether

two officers and thirty-two enlisted; actually only two killed in action have

been documented and three wounded. Adams counted nine killed and twenty-five

wounded, including Captain Luckett and two privates of Wood’s 1st Mississippi

Cavalry killed in action in the last charges near Romulus. Both opposing forces

camped around Romulus that night. Squadrons of the 2nd Michigan Cavalry, which

were engaged much of the day, did not finally go into camp until after midnight.

Adams’ command bivouacked south of Romulus.

The next morning Adams moved his brigades some fifteen miles south down the

Vienna-Northport Road to the vicinity of Hinton’s Grove. Undoubtedly the

command’s field hospital, ordnance train, and provost with prisoners had

remained in this area after the initial skirmish the day before. Here the

Mississippi and Louisiana troopers could dry out and rest their jaded mounts.

Scouts were kept out north of Romulus, meanwhile, to keep the Federal brigade

under observation as it moved back to the Northport area. Adams issued orders

for his command to move at 7 A.M. on April 8, likely to continue toward Finch’s

Ferry to join with Forrest’s corps in the Marion area, as ordered. Croxton’s men

took most of the day to move the thirteen miles back to Northport.

Late in the afternoon of April 7 some detachment of the Federal brigade must

have undertaken a reconnaissance toward the west on the Upper Columbus Road.

Adams’ scouts reported that Croxton was making forced marches on Columbus, and

at 8:30 P.M. the Confederate post at Columbus reported to Taylor’s headquarters

in Meridian some enemy forces within thirty miles of Columbus. After midnight

Adams decided he needed to immediately move his command back to Columbus, and at

2 A.M. on April 8 the Confederate brigades were saddling up and racing to

Columbus at the gallop, over Sipsey Bridge again and up the Selma-Columbus

(Lower Columbus) Road. The command began to arrive in the Mississippi town about

one o’clock that afternoon, awaiting the Federal advance which never came.

Summary of Action

This engagement is not described in most history books at all, and the works

which do mention it usually do so as an aside to the destruction by Croxton's

raiders of the University of Alabama. These usually call this the "Battle of

Romulus," though little of the action took place near that community in

Tuscaloosa County. Croxton's report seems to treat this as an inconsequential

skirmish which just happened after he decided to leave Pickens County,

inconvenienced by high rivers and rumors of Confederate forces twice his

strength. Croxton's O. R. report (Ser. 1, Vol 49, Prt. 1, p 422) does not appear

to be entirely factual on several points, neglecting to mention the 8th Iowa

Cavalry's involvement at all and grossly understating Federal casualties.

Croxton states he had thirty-four men lost, and all wounded were taken off; in

fact at least fifty-six (and perhaps 60) Yankee casualties can be documented,

and three wounded were left to the care of Adams' surgeons (one of which was a

Capt. J. H. Wilson, ironically enough). Other representations of Croxton's

report seem to be at odds with those found in diaries, letters, and the report

of the brigade adjutant, Capt. Wm. A. Sutherland. Sutherland's O. R. report (Ser.

1, Vol. 49, Part 1, p 425), written shortly after the adjutant had returned to

north Alabama following his detachment having been separated from the brigade.

Sutherland quotes a dispatch from Croxton which contradicts some particulars of

Croxton's own report. (Sutherland's detachment burned the Pickens County

courthouse in Carrollton the same day of the Adams-Croxton engagement.)

Naturally Adams left no report, but a letter written by a sergeant of the 18th

Louisiana Cavalry Battalion, Scott's Brigade of Adams' command, described the

action in detail as seen from Adams' rear (only Mississippi troops of Adams'

brigade were engaged), as well as the command's movements of several days.

Adams' losses were six killed and twenty-five wounded.

Nearly two thousand combatants were engaged in a series of cavalry fights over a

distance of some twenty-three miles over impassable roads in heavy rain. Half of

the Confederate force routed two Federal regiments, both armed to a man with

Spencer carbines, and was only halted by a determined defense from well-prepared

positions of a third regiment in growing darkness and heavy rain.

Federal losses were 50% greater than Confederate; southern cavalry held the

fields of contest at the close of fighting. That Croxton was actually driven

back northward, rather than his having decided to withdraw in that direction

prior to the Confederate attack, would seem to be the case from close

examination of the facts. Consequently this would be a tactical as well as

strategic victory for Confederate arms.

|