ELIZA SIMS AND TWO LIBRARIES

By Clinton F. Cross

6. The Cross Family in America

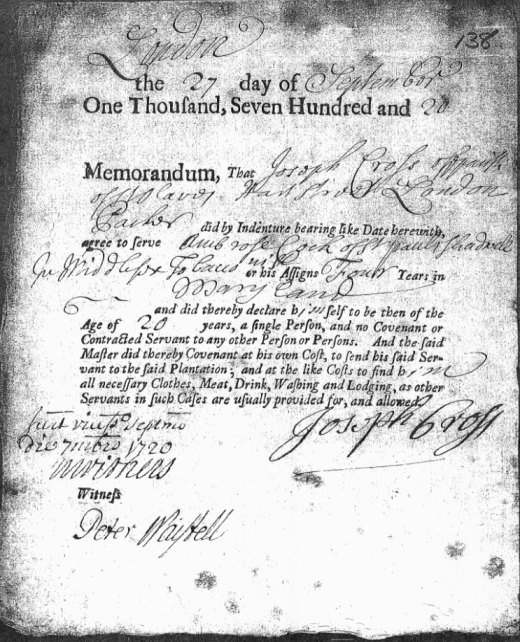

Joseph Cross (1700-1751) of “St. Olave, Hart Street, London,”

Eliza’s great-great grandfather, came to America in 1720, the year

of the "South Sea Bubble," in reality the first stock market crash

in English history. A few weeks after the market crashed, on

September 27th, he signed on as indentured servant with an English

labor broker named Ambrose Cocke. He agreed to work in a tobacco

field for four years, and Cocke agreed to pay his passage. He landed

in Essex County, Virginia. His ship captain paid for his passage,

but then in effect sold him to his future employer for a period of

at least four years.

Indentured servants usually had a hard life. They were recruited

because America was rich in land, but had few people to work the

land. Many indentured servants, like many of the slaves who

succeeded them--especially in Virginia, died. Joseph Cross survived,

perhaps because he could read and write.

Indenture Agreement, Joseph Cross 27 Sep 1720

Cross probably came for financial advancement. Cross signed up for

his voyage to America at St. Olave Church, Hart Street, in London

(founded in the 13th century, located near the Tower of London, and

still conducting services), but we don't know where he was born and

we don't know anything about his life before he came to America.

Essex County was primarily settled by Cavaliers (those who supported

the King during the English Revolution) and was very loyal to

England. The primary agricultural crop in Essex County was tobacco.

It was very different from Hanover County, which was settled at a

later date by Scots-Irish.

Joseph received a “head-right,” 50 acres of land—-to the West of

Virginia, in 1724 when he completed his indentured servitude. He

chose, however, not to accept the head-right. Instead he became a

sharecropper working for someone else.

Shortly after freeing himself of his indentured servitude, Joseph

married a woman by the name of Jane. Joseph and Jane had two

children. The oldest, Samuel, was born in 1727. Joseph the second

was born in 1731.

In 1734 Joseph the first sold his head-right to William Beverley.

In 1742 Joseph was able to purchase some land from the Reverend

Robert Rose, an Anglican minister at St. Anne's Parish in Virginia.

(Incidentally, Essex County had two parishes; most counties had

three).

The transaction was initially documented as a lease. In exchange for

the use of the land, Joseph Cross, “planter,” agreed to pay Robert

Rose, “gentleman,” an insignificant amount of money and the rent of

“one ear of Indian Corn if demanded on the Feast of All Saints.”

This transaction was not the actual agreement, but an acknowledgment

of relative social status. Another document was prepared in which

Rose sold the same property to Joseph for one hundred pounds.

With this purchase, Joseph acquired the right to vote.

In 1745 John Cheek sold Joseph Cross 62 more acres. His oldest son,

Samuel, witnessed the purchase.

In 1750 Joseph Cross purchased another 126 acres, adjacent to the

land he had purchased from Cheek.

Joseph Cross wrote his will in 1747. His will was written by the

County Clerk. Perhaps the clerk was fulfilling the role of a lawyer.

Joseph the first died in March of 1751. The estate was settled

without difficulty. Jane was not mentioned in the administration of

the estate and so it is to be assumed that she died before he did.

Three neighbors made an inventory of Joseph's property and returned

an appraisal in May of 1751.

The seven slaves who constituted Joseph's most valuable assets

ranged in value from 40 pounds each for a man named Samson and a

woman named Peg, to ten pounds for a boy named Jack. The appraisal

also noted a mare, two old sheep, a few pigs and some poultry. His

household goods included furniture, a spinning wheel, assorted rugs

and blankets, a brass candlestick, three old guns, one sword, a

parcel of books and various other items. The entire estate,

exclusive of land, was valued at 271 pounds. At the time of his

death Joseph Cross owned 458 acres of land.

On October 15th, 1751, Samuel and Joseph the second, co-executors of

the estate, returned an account for the expenses incurred in

settling their father's estate. Included was a charge of ten

shillings payable to a Mrs. Hannah Upshaw for two gallons of brandy

for the funeral.

Samuel and Joseph the second continued to live in Essex County after

their father’s death. Both married in Essex County. Samuel married a

woman by the name of Anne.

Joseph the second married Elizabeth Burke. What do we know about

Elizabeth and her family?

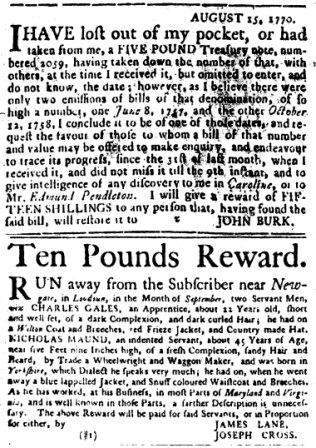

Elizabeth Burke's father was John Henry Burke; her mother was

Lettice Dannelly. John Henry Burke owned a tavern and a ferry. The

business was known as Burke's Bridge and Burke's Ordinary and it was

located on a Stage Road running through Caroline County. John Henry

Burke served food and drinks in the tavern, and charged a toll to

cross the Mattaponi River. His job gave him little social status,

but good money.

John Henry Burke and his wife had seven children, four girls and

three boys. They were a contentious lot. John Henry was brought

before the Caroline County Court on charges of assault and battery

at least once. His son Thomas was charged with assault and battery

nine times.

Joseph Cross the second, hereinafter simply referred to as Joseph

Cross, and Elizabeth Burke Cross, had many children. The oldest of

Joseph and Elizabeth's girls was Judith Cross, born in 1756.

In 1773 Judy married William Sims, Eliza’s grandfather and Nicholas

Sims’ grandfather.

One of Joseph and Elizabeth’s younger children, Oliver Cross, was

born in 1768. Judy and Oliver are important in the family history:

Eliza Harlan married Oliver’s son, Joseph Oliver Cross. And many,

many years after Eliza married Joseph Oliver Cross, Eliza (Judy

Cross’ granddaughter) married Judy’s grandson, Nicholas P. Sims.

Hard times hit Essex County in the 1750's. Samuel Cross and Joseph

Cross responded differently to Essex County’s economic depression.

Samuel decided to remain in Essex County. In 1758 Joseph and his

family moved to Hanover County, located west of Essex County.

In 1777 (the same year the British marched passed the Old Kennett

Meeting Place in the Brandywine), Joseph Cross' father-in-law, John

Henry Burke, died. John Henry's 26 slaves and substantial real

estate holdings were divided among his children and grandchildren.

In his will John Henry Burke provided that his son Thomas should not

receive any of the slaves bequeathed to him if he violated the terms

of his security, probably a peace bond that John Henry Burke had

signed for him.

Joseph Cross supported the American Revolution and was a member of

the Virginia militia. Joseph’s son Henry--one of Oliver and Judy’s

brothers—-also participated in the Revolution as a member of the

militia.

Militiamen were responsible for protecting the Tidewater region from

attack by sea. In the fall of 1778 Joseph Cross marched to

Williamsburg and then to Richneck Plantation on the Warwick River in

what is now Newport News, Virginia, to guard against an anticipated

raid by the British. He and his fellow militiamen were stationed at

Richneck Plantation for at least two months.

In 1781 General Cornwallis marched up the Carolinas and into Hanover

County. Shortly thereafter George Washington and his troops cornered

General Cornwallis at Yorktown. Of the 16,000 American and French

troops participating in the battle of Yorktown over 3,000 were

Virginia militiamen. It is likely that Joseph Cross and his son

Henry Cross were present at that event.

For many years prior to the American Revolution, Joseph Cross

attended St. Paul's Parish church, an Anglican church, connected to

the Church of England. The Reverend Patrick Henry (the uncle of

Patrick Henry the patriotic orator for independence) was the rector

of St. Paul's. Today the church is known as

Slash Church.

When Patrick Henry died, he was succeeded by a William Dunlop.

(Incidentally, the name ‘Dunlop’ is an older version of the name

‘Dunlap,’ and people with both names are probably distantly

related).

Prior to the American Revolution in Virginia, church membership was

required and the church taxed people who lived in the parish. The

church had certain responsibilities to the community: the church was

responsible for providing social services, taking care of paupers,

and caring for others in need of social assistance.

Joseph was elected a vestryman in St. Paul’s Parish Church in 1779,

and—except when he was fighting the British as a militiaman—attended

meetings regularly.

In 1784 (three years after Cornwallis surrendered to Washington)

Joseph was appointed one of two church-wardens. The church-wardens

were responsible for the safekeeping of church funds.

In 1785 St. Paul’s vestrymen agreed to be “conformable to the

Doctrine, Discipline, and Worship of the Protestant Episcopal

Church”—which was the non-taxing American successor to the Church of

England.

After 1785 Joseph Cross quit participating in church affairs. We

don’t know why.

Joseph Cross continued to acquire wealth during the Revolutionary

War. Tax records reflect that in 1782 he owned 20 slaves, 12 horses,

and 30 head of cattle. By 1790 he owned 2,200 acres of land, 1,800

acres in Hanover County and another 400 acres in Georgia.

Joseph wrote his will in November 1796, during the last year of

George Washington's administration. He died on March 18th, 1797,

shortly after John Adams was sworn in as second President of the

United States.

As previously stated, Joseph Cross and Elizabeth Burke Cross had a

number of children, including one Oliver Cross.

Oliver Cross was born in 1768. He married Sarah Harris. Oliver and

Sarah had a number of children, including Joseph Oliver Cross, but

the marriage was not a good one. It was very difficult, if not

impossible, to get a divorce in Virginia at that time (Fischer,

281-286).

When it became clear that Oliver and his wife could not live

together, Oliver’s brother--along with some of his wife's

representatives--got Oliver to go to a tavern to sign a separation

agreement. As they proceeded to discuss the agreement Oliver Cross

decided that he didn't understand what was going on, and further

stated that he wanted a lawyer to draw up the agreement. With that

demand, the meeting ended.

When the parties reconvened Oliver claimed he still didn't

understand what was happening. He finally asked his brother whether

or not he ought to sign the agreement. His brother said he should.

Without any support from his own brother, Oliver Cross signed the

agreement.

Oliver then left for Tennessee.

Years later, after his wife died, Oliver went back to Virginia and

to reclaim “his” slaves. Oliver Cross' version of the events is

stated in an answer filed in a lawsuit in the City of Richmond. His

written pleadings are somewhat detailed, basically claiming that he

was tricked out of his property.

We don't know the results of the litigation.

Oliver Cross probably died in 1834. His son Joseph Oliver Cross was

administrator of his estate and sale of his property began on

December 20th, 1834.

7. Three Families in Tennessee

In 1806 (Thomas Jefferson was President), Elijah Harlan moved to

Tennessee (his father had just died). At about the same time, Oliver

Cross, having left his wife, moved to Leeper’s Creek. William Sims,

married to Judith Cross (Oliver’s sister), purchased land near Mt.

Pleasant. They all lived close to each other, in Maury County,

Tennessee.

|